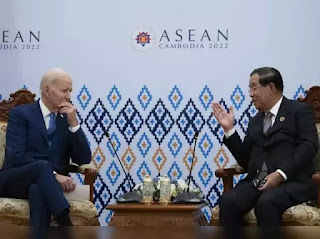

US, China And ASEAN Nations

Photo source: The Economic Times

By Naveed Qazi | Editor, Globe Upfront

In the first decade of this century, ASEAN finally addressed one of its long-standing weaknesses: its failure to include member countries’ defense secretaries in regional security dialogues. In 2006, ASEAN established a Defense Ministers’ Meeting, and in 2010, it expanded that forum to include eight dialogue partners: Australia, China, India, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Russia, and the United States. In 2017, ASEAN made this meeting a standing annual forum, significantly strengthening security cooperation among participating countries.

New multilateral organisations have emerged, seeking to take advantage of Washington’s and Beijing’s hunger for influence. One is the Shangri-La Dialogue, an annual Singapore summit hosted by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think tank based in the United Kingdom, with the support of the Singaporean government. There, top defense officials from the Asia-Pacific and beyond gather, engaging in discussions and debates on regional security matters.

Both China and the United States have had to offer incentives to ASEAN states to maintain or gain leadership in the region. For example, for 25 years, Southeast Asian leaders have longed for a legally binding international code of conduct to resolve conflicts in the disputed waters of the South China Sea. For many years, China simply resisted though it signed the nonbinding Declaration on the Conduct in the South China Sea in 2002. But in the mid-2010s, as China sought to wield institutional power through ASEAN, the organisation also pressed China to accelerate negotiations toward a code of conduct, yielding a draft negotiating text in 2018. And in 2023, against the backdrop of China’s increasing rivalry with the United States, Beijing signaled that it is ready to move quick on these issues.

The United States, in the past, has also deepened its cooperation with ASEAN though. In 2009, then President Barack Obama became the first US president to meet with all ten ASEAN heads of state as a group. That same year, the United States joined the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, a framework for the peaceful resolution of disputes in the region, and three years later, it officially joined the annual East Asia Summit. The Biden administration has collaborated with ASEAN on new health, transportation, women’s empowerment, environment, and energy initiatives and green-lighted a Department of Defense investment of $10 million annually to train emerging Southeast Asian defense leaders and foster connections between them and their U.S. counterparts.

Building on the Belt and Road Initiative, in 2015, China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as a tool to boost its regional influence. To counter those developments, the United States proposed infrastructure initiatives such as the 2019 Blue Dot Network with Australia and Japan, a project to promote the development of trustworthy standards for infrastructure. Washington followed that with the 2021 Build Back Better World initiative and the 2022 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII); both seek to provide comprehensive alternatives to the BRI.

Developing countries have benefited immensely from this competition. Through engagement with ASEAN, and following PGII frameworks, Washington committed in 2021 to investing $40 million in emerging Southeast Asian economies to help make the region’s power supply cleaner and more efficient. That investment is expected to generate $2 billion in financing.

With loans from the BRI, Laos began construction that same year on a massive $6 billion railway project, the largest public works initiative in the country’s history. More recently, Pakistan received a $10 billion loan from Beijing to upgrade its main railway network. That upgrade forms part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a BRI centerpiece with an estimated total cost of $60 billion. Although some critics have expressed concern that these loans will create debt traps for recipient countries, they are nevertheless essential for their economic development, given their limited options for infrastructure financing. The resulting economic growth contributes to peace in the region, too.

In the last few years, bilateral relations between the United States and China have degraded, recently pushing them toward the brink of a hot war over Taiwan. The task for their policymakers is to manage their rivalry so it is less tense and risky.

The United States and China will likely continue to compete for military power. But they cannot cross this competition’s redline. It would be extremely dangerous for either side to miscalculate capabilities of each other or resolve or engage in nuclear threats.

It is essential for both countries to emphasise strengthening, not weakening, their economic interdependence. So long as the United States and China are interdependent, their economic ties and the relationships between their citizens serve as guards against military escalation. These countries will compete vigorously. But their leaders must not vow to end their reliance on each other to score domestic points, as former US President Donald Trump did repeatedly. They must ensure that their rhetoric and actions do not seem to support decoupling.

Finally, it is crucial for the two countries to avoid framing their competition in ideological terms. Biden has often described the contemporary world as embroiled in a battle between democracy and autocracy. Although the Chinese Communist Party is exceptionally ideological at home, when Xi speaks to other countries, he never characterises China’s competition with the United States as an existential battle between irreconcilable worldviews. If Biden has, at times, tried to be an ideological boxer in foreign affairs, Xi prefers ‘tai chi’, avoiding direct contact.

Xi’s approach in this regard is the better one, and US leaders should emulate it. The reality is that a number of Asian countries—such as Singapore and Vietnam—neither have nor want systems modeled on that of the United States. Chest-beating about democracy can alienate people who have watched US democracy falter at home. Xi’s rhetoric avoids suggesting that other countries must ally themselves ideologically with China in order to cooperate with it, leaving space for them to benefit from and keep the peace with both Beijing and Washington.

Comments

Post a Comment

Advice from the Editor: Please refrain from slander, defamation or any kind of libel in the comments section.